Every profession evolves. Tools improve. Informatoion becomes faster. Expertise becomes more specialised.

The uncomfortable question is this:

At what point does failing to use the best tools available become negligent rather than merely old fashioned?

For insolvency practitioners, accountants, lawyers and other trusted advisers, this is no longer theoretical. Artificial intelligence, structured diagnostics, specialist referral networks and data-driven systems now exist. They are not experimental toys. They are operational tools.

So where is the line?

1. The Legal Test Is Not ‘Best Practice’

Negligence in English law is not measured against perfection.

It is measured against what a reasonably competent professional would do in the same circumstances.

Historically that meant:

- Acting in accordance with a responsible body of professional opinion.

- Exercising reasonable skill and care.

- Staying within your competence.

But here is the tension.

If a tool exists that materially improves:

- Accuracy

- Speed

- Risk detection

- Regulatory compliance

- Documentation quality

… then at some point the ‘reasonable professional’ standard shifts.

When the majority of competent practitioners adopt a tool because it reduces error and increases reliability, ignoring it begins to look less like personal preference and more like avoidable risk.

2. Ignorance Is Not a Defence

There is a difference between:

- Choosing not to adopt a tool after considered analysis

- Being unaware the tool exists

- Dismissing it without understanding it

The first is defensible.

The latter two are dangerous.

In regulated professions, a duty of continuing professional development exists for a reason. If technology fundamentally alters how risk is assessed, how fraud is detected, or how options are analysed, then failure to understand those developments may itself fall below reasonable standards.

The law does not require you to use the newest system.

But it does expect you to remain current.

3. The Referral Dilemma: When Does Introduction Become Exposure?

Now consider the harder issue.

You introduce a client to:

- A specialist tax adviser

- A restructuring consultant

- An insolvency practitioner

- A claims company

- A litigation funder

- A turnaround adviser

Where is your responsibility?

There are several competing arguments.

Argument A: ‘It’s the Client’s Choice’

Some professionals take the view:

I made an introduction. The client chose to proceed. My responsibility ends there.

This is weak.

If you hold yourself out as a trusted adviser, your introductions carry implicit endorsement. You cannot pretend you are neutral if the client relies on your judgement.

If you have not:

- Checked credentials

- Understood methodology

- Reviewed conflicts

- Assessed competence (and continually, not just one-off)

… then you are exposing your client to risk without due diligence.

That may not always be negligence. But it may be.

Argument B: ‘I Cannot Monitor Another Professional’

True. You are not expected to supervise another regulated expert.

But you are expected to:

- Make referrals within a reasonable competence framework

- Avoid obvious red flags

- Intervene if advice appears clearly flawed

- Clarify the limits of your responsibility

Blind trust is not professional oversight.

If a specialist’s advice conflicts with basic commercial logic or legal principles, you cannot simply look away.

Argument C: ‘The Client Should Choose Their Own Expert’

There is merit in allowing independence.

But ask yourself:

If your client lacks the technical ability to assess the specialist’s competence, are you genuinely empowering them … or are you abandoning them?

Trusted adviser status implies stewardship.

If you wash your hands completely, you are no longer advising. You are facilitating.

That is a different role.

4. When Does It Become Negligent?

There is no single line. But several red zones exist.

It may cross into negligence where:

- A tool materially reduces known risks and you ignore it without reason.

- A specialist is introduced without reasonable due diligence.

- Obvious warning signs are disregarded.

- Conflicts of interest are not examined.

- You benefit financially from a referral without transparency.

- You fail to reassess advice when circumstances change.

Negligence is often not a single dramatic mistake.

It is cumulative passivity.

5. The AI Question

Now apply this to modern AI systems and structured review tools.

If AI can:

- Flag financial distress earlier

- Identify legal risk patterns

- Improve documentation consistency

- Detect anomalies

- Suggest restructuring pathways

- Reduce cognitive bias

… then is choosing not to use it negligent?

Not yet automatically.

But consider this carefully.

If an error occurs that AI would almost certainly have caught, and the tool was widely available, affordable and routinely used by competent peers, a claimant’s barrister will ask a very simple question:

Why did you not use it?

Your answer must be better than ‘I don’t like new things.’

6. The Human in the Loop

This is critical.

Using tools does not remove responsibility.

It shifts responsibility.

Negligence may also arise from:

- Blind reliance on automated output

- Failure to challenge AI conclusions

- Delegating judgement to software

Professional judgement remains human.

The safest position is not:

- ‘I don’t use technology.’

Nor - ‘I rely on technology.’

It is:

I use the best available tools to enhance my judgement, not replace it.

That is defensible.

7. The Trusted Adviser Standard

I often speak about the type of insolvency practitioner the profession should attract. The same applies to other professions.

Empathetic.

Curious.

Intellectually engaged.

Committed to learning beyond minimum CPD.

That standard implies something deeper than technical compliance.

It implies stewardship of clients’ futures.

If better diagnostic tools exist, and you ignore them, are you meeting that standard?

Perhaps legally.

Possibly not ethically.

And over time, ethical drift becomes legal exposure.

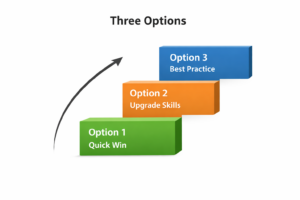

8. A Practical Framework

To protect yourself and your clients:

- Periodically review available tools in your sector.

- Document why you adopt or reject them.

- Conduct due diligence on referral partners.

- Clarify referral boundaries in writing.

- Maintain oversight without micromanaging.

- Intervene where advice appears flawed.

- Keep learning.

That is not perfection.

It is professional maturity.

Final Thought

Negligence rarely begins with bad intent.

It begins with:

- Assumptions

- Habit

- Complacency

- Overconfidence

The line is crossed when you stop asking:

Is this still the best way to serve my client?

In a world where tools evolve rapidly, the safest professionals are not the most conservative or the most aggressive.

They are the most curious.

And the most accountable.

Hashtags

#ProfessionalStandards #Insolvency #Accountants #LegalRisk #TrustedAdviser #AIinPractice #Governance #Ethics #VAi

Try VAi now.